Here Abano introduces the subject matter and the names and main qualities of the sixteen figures.

Geomancy is a simple science to master. It employs the same methods of astrology to answer any question the person might have—whether what one wants to undertake will meet with success or not, according to natural virtue and celestial influence.1

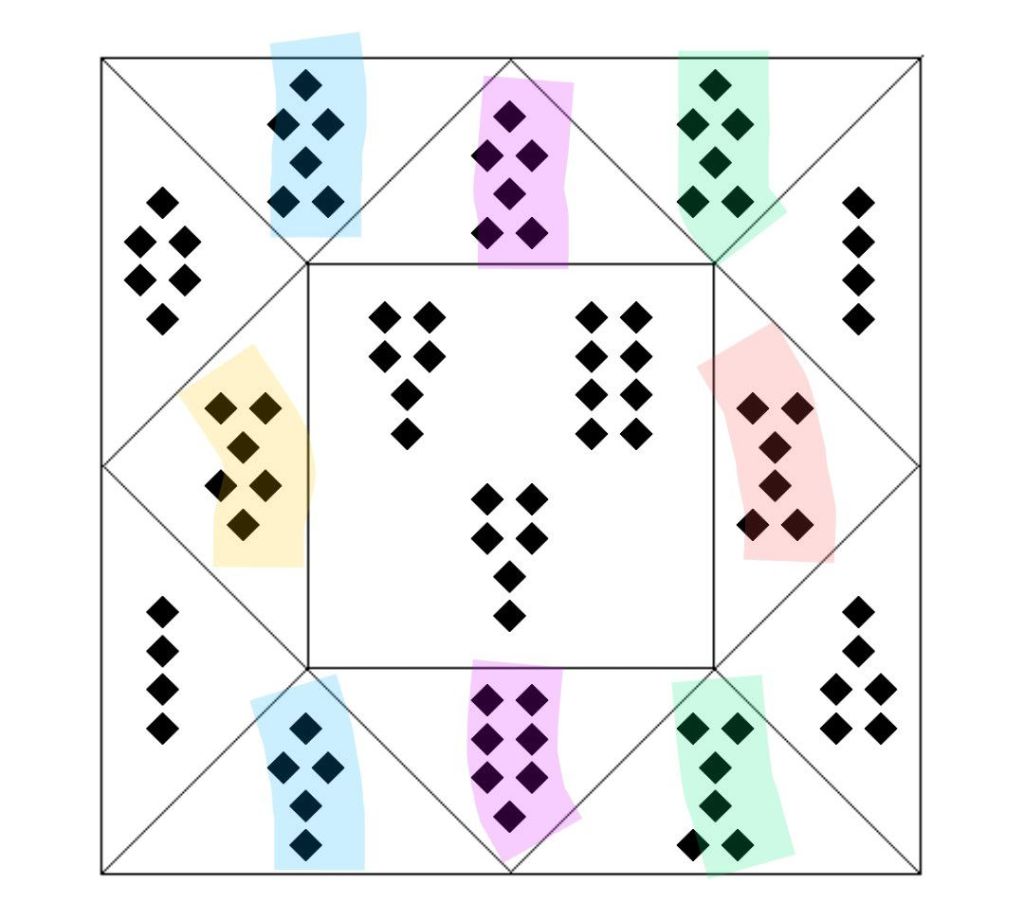

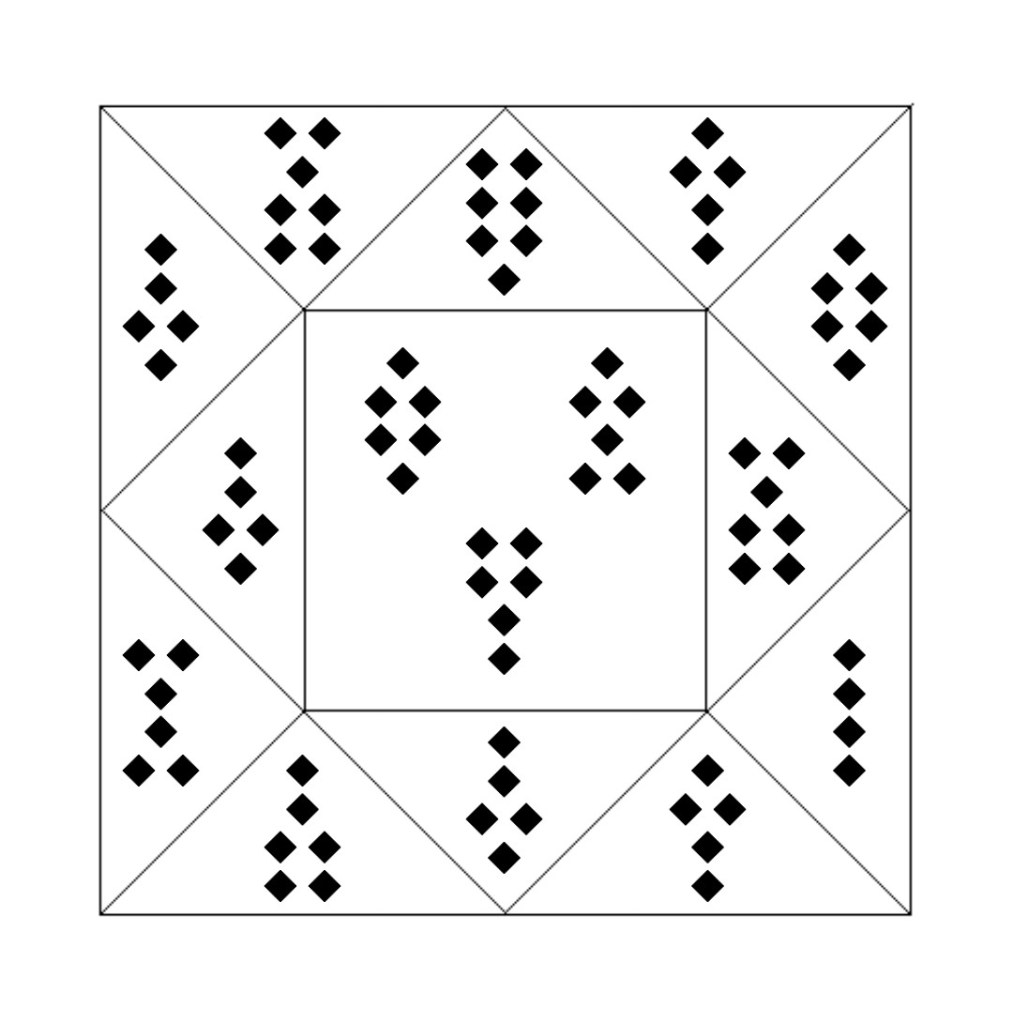

This method of judging [questions] and receiving information avails itself of four figures made of ink points on a piece of paper by the Geomancer’s hand, which is moved by the heavenly influence of God’s eternal grace.2 As such, one must ask one’s question with sincerity and a pure soul.

From the initial four figures, sixteen are derived (and no more than sixteen) to answer any question the person might desire to know [the answer to]. However, not all the figures are necessary in answering a specific question. Only fifteen are, and they are enough to answer any question.3

These fifteen figures don’t always come up in the same way, but only as Heaven influences them to come up.4

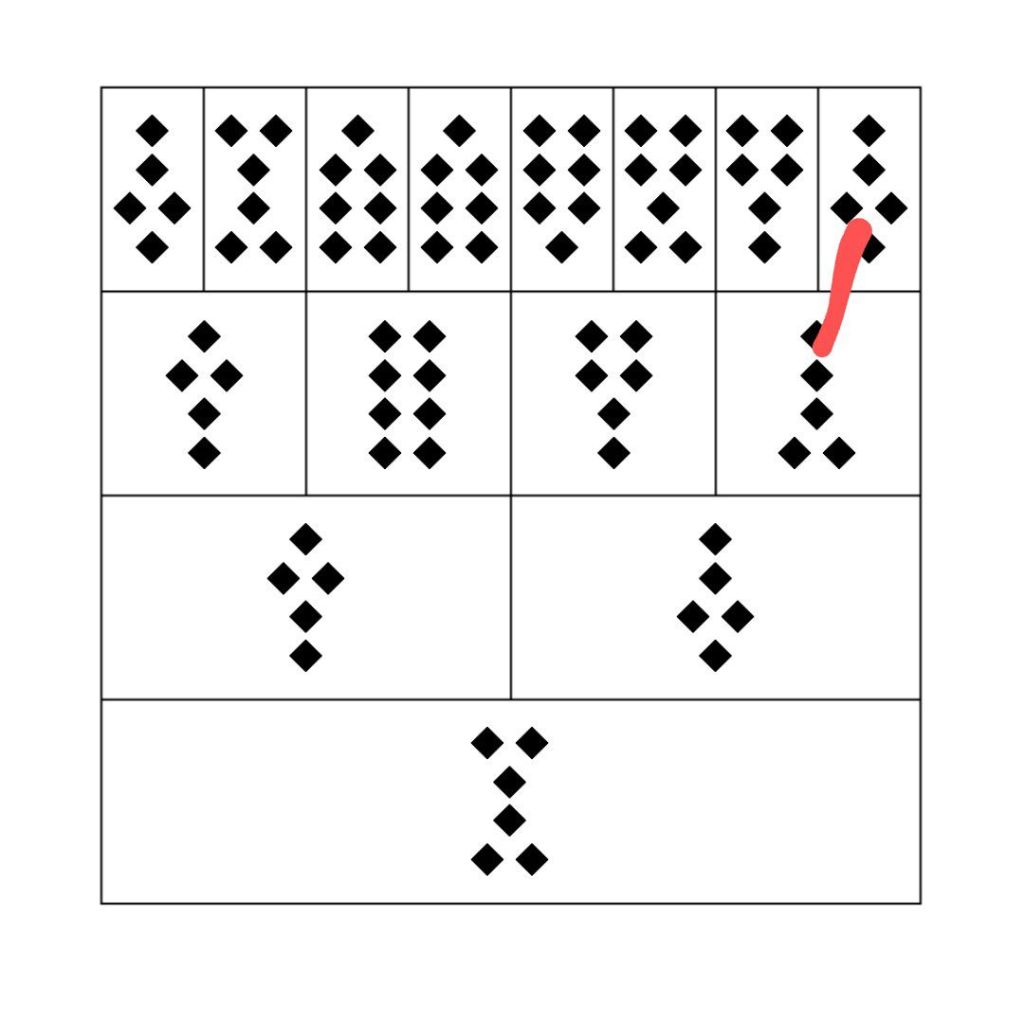

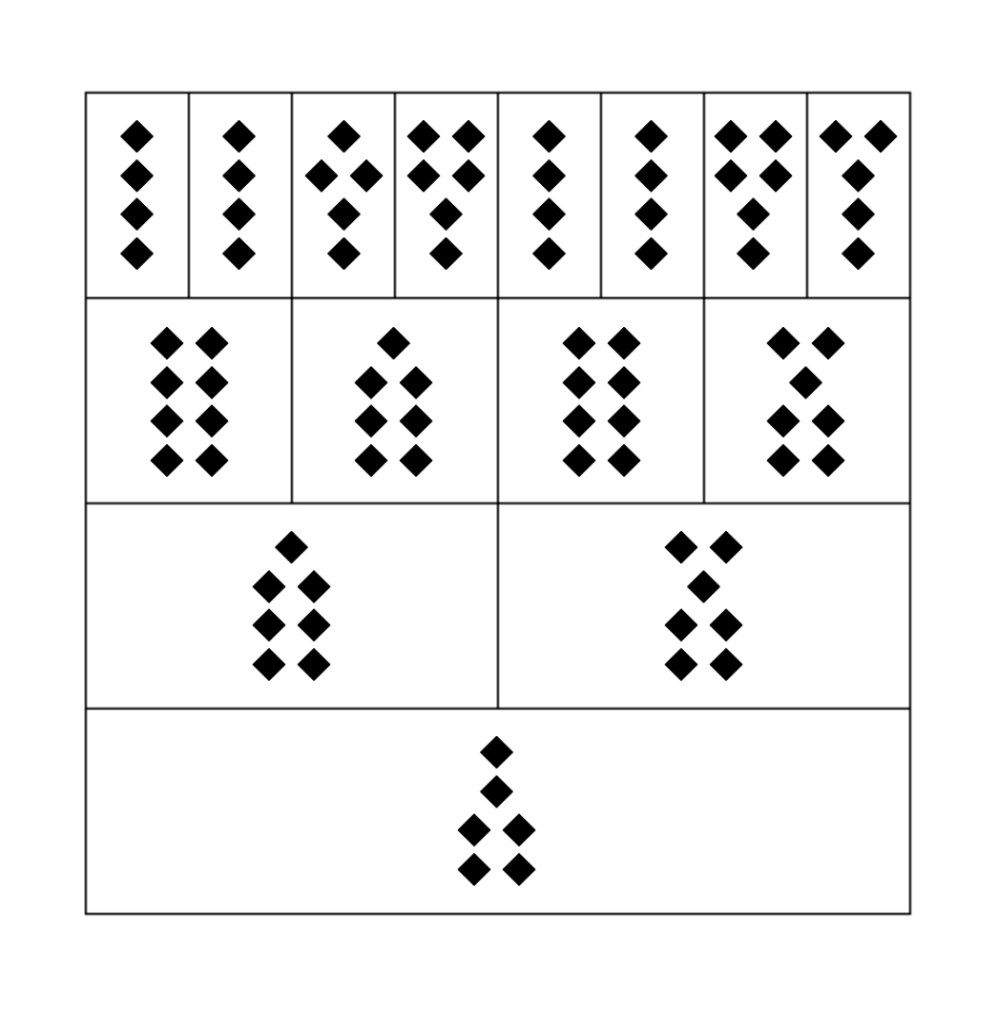

These are the sixteen figures and their names:

Four figures are assigned to each quadrant of the Heaven (North, South, East, West) and to the four elements (Fire, Air, Water, Earth) as will become clear shortly. They are called fortunate or unfortunate.

Rubeus, Amissio, Fortuna Minor and Cauda are Fiery, that is, hot and dry, and of choleric complexion,5 southern, diurnal, masculine, strongly malicious, haughty and furious.6

Acquisitio, Laetitia, Conjunctio and Puer are airy, that is, hot and wet, of sanguine complexion, eastern, masculine and diurnal, very good and temperate, and good wherever they fall in the chart.7

Puella, Populus, Via and Albus are cold and wet, of phlegmatic complexion, northern, feminine and nocturnal. Generally fortunate and good where they fall in the chart.

Caput, Fortuna Maior, Tristitia and Carcer are earthy, that is, cold and dry, and of melancholic complexion, western, feminine, nocturnal. Two are good, Caput and Fortuna Maior, while two are bad, Tristitia and Carcer. They are slow and slothful in their meanings, but they cause what they promise nonetheless.

All the above is to be noted when a figure represents a person and another figure a different person, that we may know their character and how well they may get along.

The sixteen figures have yet another cycle of attributes that renders them positive or negative. Depending on whether they are mobile or fixed, we may know how soon or how late the effect will manifest, and how the situation shall be resolved according that they are entering or exiting or mixed.

Acquisitio, Fortuna Maior, Albus, Caput, Puella and Tristitia are entering, fixed, good and fortunate, except Tristitia, which is always bad.

Amissio, Fortuna Minor, Rubeus, Cauda, Puer and Laetitia are exiting, mobile, bad and malicious, except Letitia, which is always good.

Populus, Via, Conjunctio and Carcer are said to be common, that is, neither very quick nor very slow, and they are also neither too good nor too bad, though they tend to err on the side of goodness, except for Carcer, which is always evil.8

And yet another meaning must be added, which shows whether the people signified by the figures conform to one another in terms of will and soul, according that the figures are mobile, quick or slow, and according that they are single-bodied or accompanied [double-bodied].9

Acquisitio, Fortuna Maior, Puella, Caput, Tristitia and Albus are fixed, single-bodied and regular.

Amissio, Puer, Cauda, Letitia and Rubeus are mobile, half-bodied and diminished.10

Fortuna Minor, Carcer, Conjunctio, Via and Populus are common, that is, between mobile and fixed, and they are neither too quick nor too slow, and are double-bodied and accompanied, except for Via.

And in order that one may easily know the virtue and influence of the Heavens through the sixteen figures, we must also note their correlation with the twelve zodiac signs. Similarly, they are attributed to the seven heavenly planets, according to their influence on the twelve signs.

However, each figure does not mean the same as the other [assigned to the same planet]. Each has a separate meaning. As such, Carcer is Saturn direct, Tristitia is Saturn retrograde; Acquisitio is Jupiter direct; Letitia is Jupiter retrograde; Rubeus is Mars direct, Puer is Mars retrograde;11 Fortuna Maior is the Sun when elevated, Fortuna Minor is the Sun when depressed and obscured; Puella is Venus direct, Amissio is Venus retrograde; Albus is Mercury direct, Conjunctio is Mercury retrograde; Populus is the waxing Moon, Via the waning Moon. Consequently, the direct signs are better than the retrograde. Furthermore, Caput is attributed to Jupiter and Venus, Cauda to Saturn and Mars.12 But this is not always the case, but rather depends on the question asked.

MQS

Footnotes

- The concept of natural virtue underpins the Western magical worldview. The word ‘virtue’ must not be understood in a moral sense, but rather in the sense of ‘property’ or ‘power’. It forms part of the Hermetic doctrine of Signatures. The virtues of the things under the Heavens are generally seen as corresponding to certain celestial factors. ↩︎

- This is a rather typical phrasing found in various premodern handbooks. It is connected with the Christian Aristotelean worldview prevalent at the time, whereby God, the unmoved mover, ruled the world not directly, but through a series of concentric spheres, each one corresponding to a planet, except the sphere of the fixed stars and that of the primum mobile. ↩︎

- The sixteenth figure is what is commonly referred to as the Judge of the Judge, formed by the Judge plus the first Mother. ↩︎

- In other words, they are ‘random’. ↩︎

- The word ‘complexion’ is used in a slightly different way from today. It refers to the theory of the four humors (black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm). These humors influenced not just the character, but also, up to a point, the appearance of the subject as well as their being prone to this or that illness. ↩︎

- Abano seems to include Fortuna Minor among the malicious figures, though later in the text he treats it as generally positive. ↩︎

- Abano however does not always treat Puer as a positive figure. ↩︎

- In all this section Abano seems to be painting with a very broad brush, talking of the figures as “always good” or “always bad”. Of course things get more complicated. ↩︎

- This is borrowed, as so much in geomancy, from astrological practice, where the mutable signs (Gemini, Virgo, Pisces and Sagittarius) are also called double-bodied. Double-bodied signs, and therefore geomantic figures, can indicate the involvement of more than one person. ↩︎

- The concept of half-bodied does not, to the best of my current knowledge, come from astrology, but I may be wrong. ↩︎

- This seems prima facie counterintuitive, as a retrograde planet is generally considered worse than a direct one, and Puer is generally not considered worse than Rubeus. ↩︎

- This is in accordance with the relatively standard Medieval practice of attributing the North Node of the Moon to the two benefics, Jupiter and Venus, and the South Node to the two malefics, Saturn and Mars. This practice developed over time and does not seem to originate in older astrology of the Hellenistic period, when both nodes appear to have been considered more or less malefic, when considered at all. ↩︎