Geomancy has changed a bit since Medieval times, but one thing that remains constant is how a Geomantic figure or Geomantic Shield is formed. This is done in order to answer a question.

As I said in the previous article, we don’t draw the whole figure in the same way. We can divide the process in two parts: the creation of the four Mothers on one side; and the deriving of the rest of the figure from the four Mothers on the other side. The first is the “divinely inspired” part, i.e., the part where you allow chance into your life, while the second part is automatic and fixed and will follow with mathematical rigor from the first.

So, how do we get a set of four Mothers? In reality, Geomancy is a rather flexible oracle, as any method is technically valid. Once you are well versed in the main operations required to draw a Geomantic figure, you can pretty much use any method that suits you in order to obtain the four mothers.

Still, some methods are more traditional than others. It seems that the Arab Magi used a stick to poke points in the sands of the desert, a method that is still perfectly valid and has even been accepted and adapted by the Golden Dawn. By the time Geomancy reached Europe in the Middle Ages, it was customary to use a stylus or pen and a tablet or piece of paper or parchment. Dice were also used, and one could, and can use dried beans or pebbles or playing cards. Anything that can give you odd and even numbers will do.

Needless to say, some have devised software that calculate everything automatically. I don’t particularly trust this method, and yes, partly it’s because technology is still so new that my mind doesn’t accept it as a valid substitute for things that are more dependent on my direct manipulation–it may very well be that in five hundred years occultists will use geomantic software without thinking twice about it, but we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.

The Pen and Paper Method

My personal favorite method remains pen and paper. I almost always use it, and I find it has an odd beauty, even power to it. It also reminds me of a playful oracle that we used to use as kids in middle school and high school in Italy to answer yes or no questions. Usually, some love-stricken teen would ask the fateful question, “does he love me?” and would start drawing random numbers of points on a piece of paper. Then she would pair up the points until either one point was left (yes) or none at all (no). I have no idea how this oracle originated, but I remember it being very much in vogue when I was a kid.

A set of geomantic Mothers is obtained in a similar, albeit more complex, manner. First off, it pays to write down the question. This has the incredible advantage that it forces you to think about it seriously, and it also makes it more real and objective.

Then, after concentrating on the question, you should ask for divine help. I’m not saying this to be preachy. Consult any Medieval handbook of Geomancy and you will find the same instruction: it’s the “Unmoved Mover” that sends his “vertue” down from the skies to answer your question. At the very least, you should take a moment to relax.

Once you feel ready, start drawing sixteen consecutive rows of points. Try to be orderly, but don’t worry too much: as long as the rows don’t cross or merge you are fine. Also, I have found that it is better to draw I’s instead of points, for the simple reason that it makes it easier to recognize the marks instead of leaving you wondering “is it a point or a random inkblot?”

Do not count the points or I’s you are making, and do not bother counting the rows as you make them. Do not engage in any kind of mathematical or rational thinking. In fact, I have found it pays to write down numbers from 1 to 16 before starting the operation, so as to be free from the worry of drawing too many or too few rows of points. Still, in the traditional instruction, you are normally told not to bother if you end up with an extra row of two–just go overboard and then discount the extra ones. Either way you will end up with something like this:

- 1) IIIIIIIIII

- 2) IIIIIIIIIIIII

- 3) IIIII

- 4) IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII

- 5) IIIIIIII

- 6) IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII

- 7) IIII

- 8) IIIIIIIIIIIII

- 9) IIIIIIIIIIIII

- 10) IIIIIIIIIIIIIII

- 11) IIIIIIIIIIII

- 13) IIIIIII

- 14) IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII

- 15) IIIIIIIII

- 16) IIIIIIIIIIIIIII

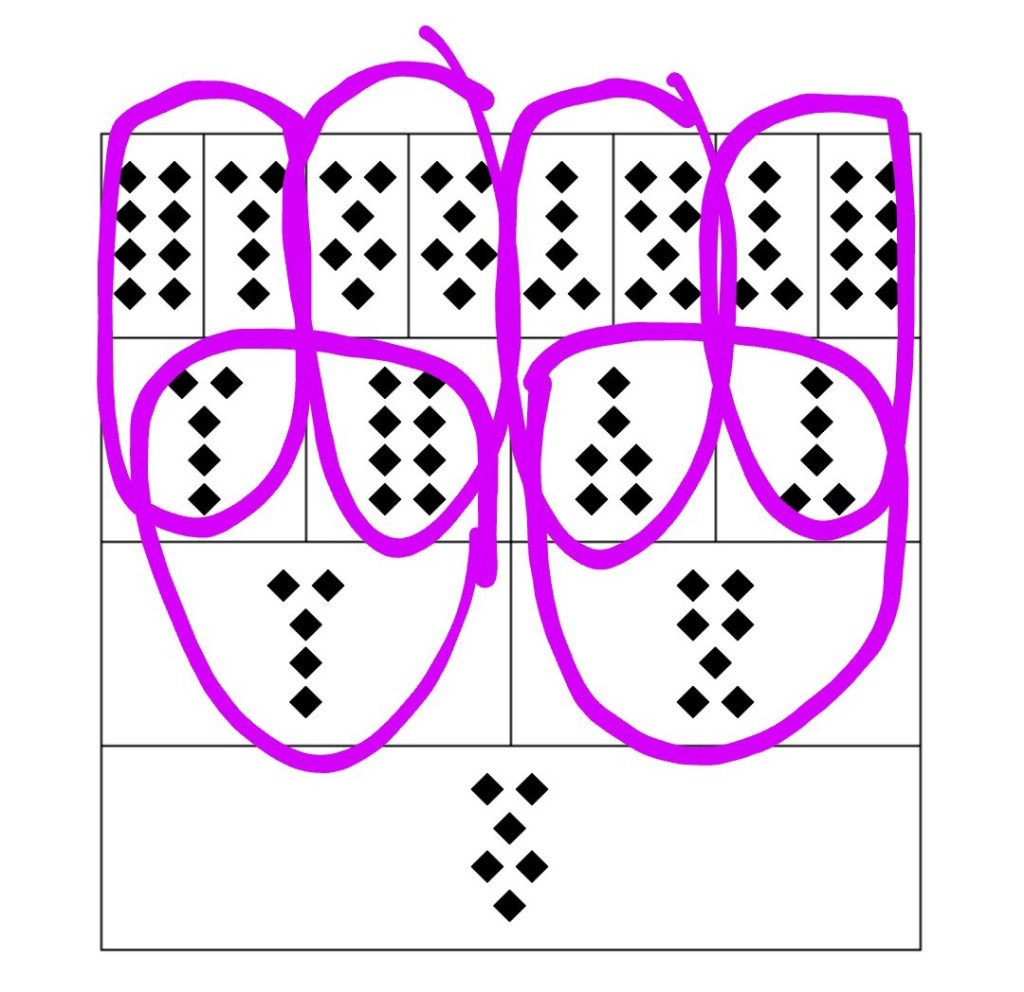

Once this operation is over, you have your four Mothers, but only in a raw form. Each Mother figure is made up of four rows (4×4 = 16). Now you need to pair up the I’s in each row until either one is left over or two. Let’s make the example of the first Mother, which is made up of rows 1 through 4:

- 1) I-I I-I I-I I-I I I = O O

- 2) I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I = O

- 3) I-I I-I I = O

- 4) I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I-I I I = O O

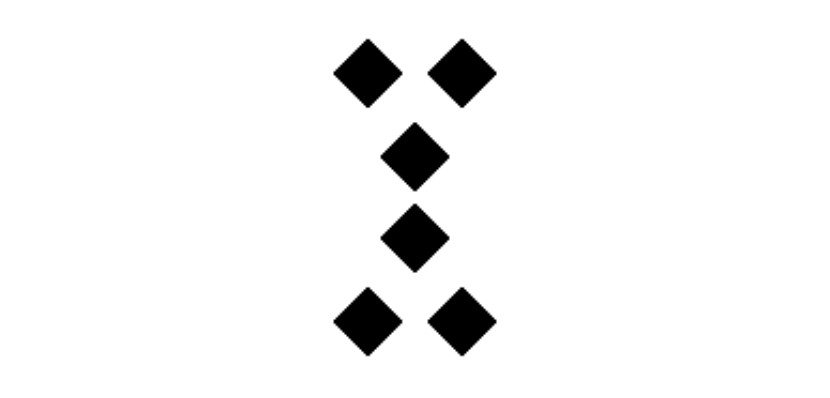

The figure we have received as first Mother is comprised by a sequence of two points on top, then one point, then one point, then two points. The same process of pairing up must be done for all sixteen rows to obtain the four Mothers (the second Mother being made up of rows 5 through 8, etc.) The first Mother we have obtained is called Conjunctio.

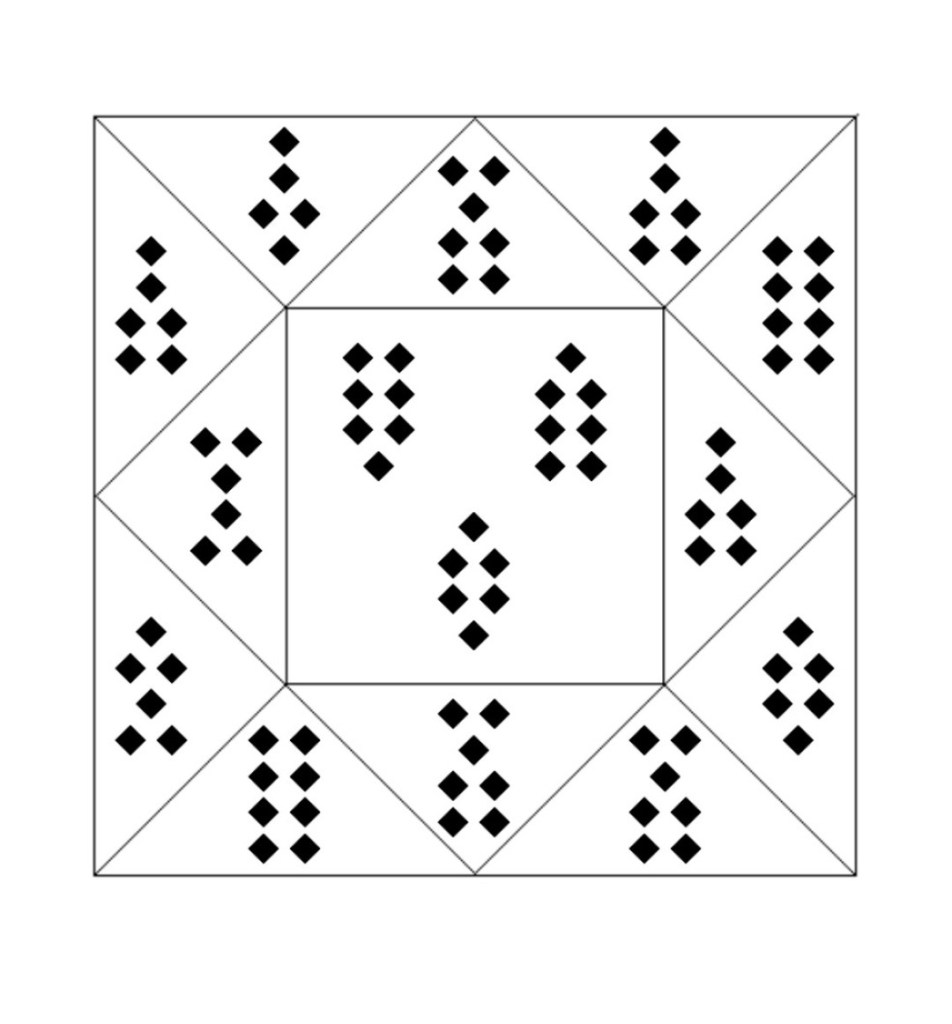

Once this operation is over, you will be left with four figures, each made up of four rows of either one or two points. From these figures you will need to derive the rest of the chart, which I will go over in the next post.